Keen to engage in a game which is fun, childish and uproots and subverts expectations and rules and is nearly impossible to play – and is truly pointless? Then play a Running-Game, now. In such a game-art-with no-point, we set up rules which we then ourselves overturn. There is no ‘end’ – no reward, no finishing line. There is also no point – no score, no purpose. It’s brilliant. Kai first conceptualised this project in 2011.

WHAT’S A GAME?

A ‘game’ is ‘a physical or mental competition conducted according to rules with the participants in direct opposition to each other’, or an ‘activity engaged in for diversion or amusement: play’ (Merriam- Webster Dictionary 2012a). Matching both definitions, running is a game. We can run against other people competitively, or for fun. ‘Fun’ is a keyword for runners. Running experts Benyo and Henderson quipping how they find saying the word ‘fartlek’, which refers to a training technique, ‘so much fun’ (2001, p.111). Also, you must have enjoyed running as a kid. It was when our parents and teachers reprimanded ‘No running! Walk!’, that we left running behind. Grown-ups must have feared us running away from their reins. Running again as adults, we may re-capture that wayward freedom. Aged forty- five, runner George Sheehan re-learnt how running was ‘fun’ and was about ‘play and enjoyment’:

‘Like most distance runners I’m still a child. And never more so than when I run’. (1978, p.211)

Running may be our ‘true journey’ ‘back to our childhood’. That is to say, the process of running may momentarily transport us back to re-live the joy of being a child. Sheehan further adds that like ‘most children, I think I control my life’. In other words, running may enable us to re-claim diversion, amusement, and a child-like freedom. It may also empower us to feel in control.

WHAT’S AN ART GAME?

Artist Corrado Morgana, known as an ‘incorrigible gamer’ (Catlow 2010, p.86), talks about ‘artgame’, which he defines as:

‘an independent or commercial game which expresses its “artness” through its play mechanics, narrative strategies or visual language’. (2010, p.9)

Based on a popular game Unreal Tournament, Morgana’s CarnageHug (2007) features player pawns inexplicably ‘killing’ one other. Mathias Fuchs, a artgame pioneer, describes CarnageHug as ‘ridiculous massacre without player-based gameplay objectives’ (2010, pp.54-59). Morgana’s artgame is an ‘interactive experience that draws on game tropes’, but detourns – ‘uproot and subvert’ – ‘mainstream game expectations’. Strategies that these artistic games use include ‘non-mainstream narratives’ and ‘experimental gameplay’.

WHAT’S A GAME ART?

Morgana defines detournement, which originates from the Situationist International, as the ‘overturning of established order’ (2010, p.7). Indeed, artists have long flirted with game tropes. Curator Daphne Dragona traces the line-age to the ‘playful spirit’ of the Dadaist, Surrealist and Fluxus (2010, p.27). Unlike Scrabble or Catch, some of these artworks, such as Yoko Ono’s 1966 White Chess Set, are ‘impossible to play’. Such works are sometimes called ‘game art’ (or ‘Game Art’). Morgana explains that unlike an ‘artgame’, this is not a game per se, but is:

‘art that uses, abuses and misuses the materials and language of games, whether real world, electronic/digital or both. The imagery, the aesthetics, the systems, the software and the engines of games can be appropriated or the language of games approximated for creative commentary’. (2010, p.12)

IS RUN LOLA RUN A GAME ART?

Tom Tykwer’s Run Lola Run (1999) seems to fit the description of a game art. In the film, ‘Lola’ runs and solves problems in three different ways.* How Lola transforms her own fate reminds me of the Daoist dictum, ‘My destiny is within me, and not in Heaven!’ (Schipper, 1994). With its energetic editing, non-linear plot, use of animation, vivid mise-en-scene and breathless techno-soundtrack, Lola’s world resembles that of a video game. Even if the runner’s high is not explicitly acknowledged, the vibrancy of the aesthetics, as well as the striking post- punk mien of the protagonist make the film exudes an infectious euphoria.

* In the film, Lola’s (weak) boyfriend, Manni, runs into trouble with the mafia and runs to her for help. They must come up with 100,000 German marks in 20 minutes. This, the premise of the film, is explained in the first twenty minutes. The subsequent 60 minutes of the film (with a crisp total running time of 80 minutes) is divided into 3 equal parts of 20 minutes each, as we breathlessly follow Lola running across the streets of Berlin, in almost real-time, as she works out three distinct solutions. In the first outcome, Lola dies; in the second, Manni dies. The third and final variation ends of a high as our heroine finds 100,000 marks and saves the day and her boyfriend.

WHEN DOES A GAME ART BECOME TRULY POINTLESS?

As for a game art that is not just user-unfriendly but pointless, Bill Viola’s 2007 The Night Journey fits the bill. The digital game is called ‘one of the most bizarre’ ever (cited in Viola 2007). According to curator Heather Corcoran, this is ‘quite different from the fast-paced, shoot-‘em-up world of a typical video game’ (2010 p.20). Instead of jewels or a damsel-in- distress, Viola’s protagonist seeks ‘enlightenment’. The game features ‘no winning and no scoring’ either. Viola’s game is thus ‘pointless’, with neither score nor ‘end or object to be achieved’ (Merriam-Webster Dictionary 2012c). That his game – like his video installations – is characterised by a meditative gait adds to its sense of meaninglessness for many players. The writer of Is Google Making Us Stupid Nicholas Carr talks about how the internet has moved us ‘away from attentive, contemplative thought’ (cited in Murphy 2011). This can be why some gamers mistake Viola’s game as ‘broken’ (Corcoran 2010, p.20). They smash the buttons ‘in hopes of eliciting some kind of quicker reaction before giving up entirely’. Even for those who ‘understand the game’s pace’, they ‘don’t have the patience to see it through’. That is why Viola’s game is tagged as ‘experimental’ (Sheets 2010), the same way his videos run parallel with the mainstream television and cinema.

ULTRA-POINTLESS: THE ULTRA-RUNNING RACE

The long-distance running race, particularly the ultra-running race of more than 26 miles, resembles a point-less game. Top sprinters complete a 100-metre race in 10 seconds. Yet, ultra-runners take ‘24 even 48 hours’, if not weeks (McDougall 2009, p.85). The awards – if any – are rubbish. The winner gets the ‘same belt buckle as guy who comes in last’.

BEYOND POINTLESS: TEH-CHING HSIEH’S OUTDOOR PIECE

Nonetheless, maximum points go to performance artist Teh-Ching Hsieh. A critic analyses that the point of his seminal Outdoor Piece is ‘extreme deprivation’ (Smith 2009). In this work, the Taiwanese-American (born 1950) roamed Manhattan for a year, 1981-1982. He seemed to be on the run, in what he explains in a original interview conducted by this writer, was a ‘freedom of exile by my own choice’ (2013). Could this be interpreted as his response – if an over-enthusiastic one – to 17th century French mathematician Blaise Pascal’s dictum about human beings’ unhappiness stemming from being locked indoors (1999, Thought 132)? So extra-ordinary this was – sleeping outdoors even as the East River froze, for instance – that another critic says that Hsieh demonstrated his ‘willingness to give his life to art’ (Sontag 2009). Yet, Hsieh would be too wise to sacrifice himself for art. Asked what his work is ‘about’, he declares that they concern ‘wasting time and freethinking’ (2012a). Just as many make the killing of zombies and pigs their occupation and pre-occupation, killing time is Hsieh’s point. Indeed, do we all not kill time before our time runs out – except that we call it ‘living’? Hsieh’s example help us draw out another meaning of ‘game’, which is a ‘procedure or strategy for gaining an end’ (Merriam-Webster Dictionary 2012a).

FOLLOWING IN HSIEH’S FOOTSTEPS: KAIDIE

Kaidie’s 1000-Day Trans-Run 12.12.2009 – 09.09.2012 is an example of a game-art-wth-no-point. This was a large body of artwork in a range of medium that Kai made to complement her PhD written thesis conducted at the Slade School of Fine Art. ‘Kaidie’ was the character played by Kai. It was through this framework that Kai picked up running, and learnt about it first hand or rather first feet as she wrote about it in her PhD thesis. ‘Trans-running’ was the name she gave to her notion of the physical and poetic processes of running. The story of Kaidie – and Kai – was that she ran in search for the quixotic ‘A / The Point of Life’. She did so not just in the city of ‘Nondon’ (which was based on London), but in the new worlds opened up by the internet. Additionally, she had a time-limit of 1000-days, and died on the last day of the ‘Nondon Olympics’ on 09.09.2012.

Kaidie/Kai was less Lara Croft – the heroine of popular game Tomb Raider – than Lola. Like Lola, Kaidie/Kai wanted to have an insight about her crises – of looking for ‘A/The Point Of Life’, for instance – through running and to metaphorically run – govern – her world. Yet, this game was virtually un-playable. ‘A/The Point of Life’ was never explicitly defined. Kaidie/Kai was also less heroine and more of an ‘action figure’. Kaidie/Kai mobilised her body to engage in ‘actions’, as well as employed the ‘figurative’ in her approach and, most importantly, resembled an ‘action figure’ or cartoon, given the absurdity of her task and approach. Furthermore, Kaidie’s Trans-Run, like CarnageHug, features death. This fulfills the game expectation of violence. Yet, the audience were told that the protagonist ‘MUST die’ on a pre-determined date. By being upfront, Kaidie/Kai deprived them the pleasure of discovering this information by themselves. By detourning game tropes, this work acknowledges and critiques what Morgana describes as the ‘cultural ubiquity’ of digital games, and demonstrates that the game aesthetics can be ‘approximated for creative commentary’. In this way, Kaidie/Kai aimed to re-claim amusement from the global phenomena of games like Angry Birds for her own world. Embodying Lola’s ‘ballsy-ness’, Kaidie/Kai ran her own courses to seek her point of life, and determined her own fate – including her death. Kaidie’s Trans-Run must have felt slow to people adapted to the rhythms of instantaneous internet alerts. Participants were also unclear about what they were ‘in direct opposition to’, or what they were in ‘competition’ against. An ultra-running race brings ‘no fame, no wealth, no medals’ (McDougall 2009, p.85). Likewise, this quest brought no end – except death, which was guaranteed on ‘09.09.2012’.

Perhaps, then, the ‘point’ of living life as a game is to reach our end-point, or end-game, of death.

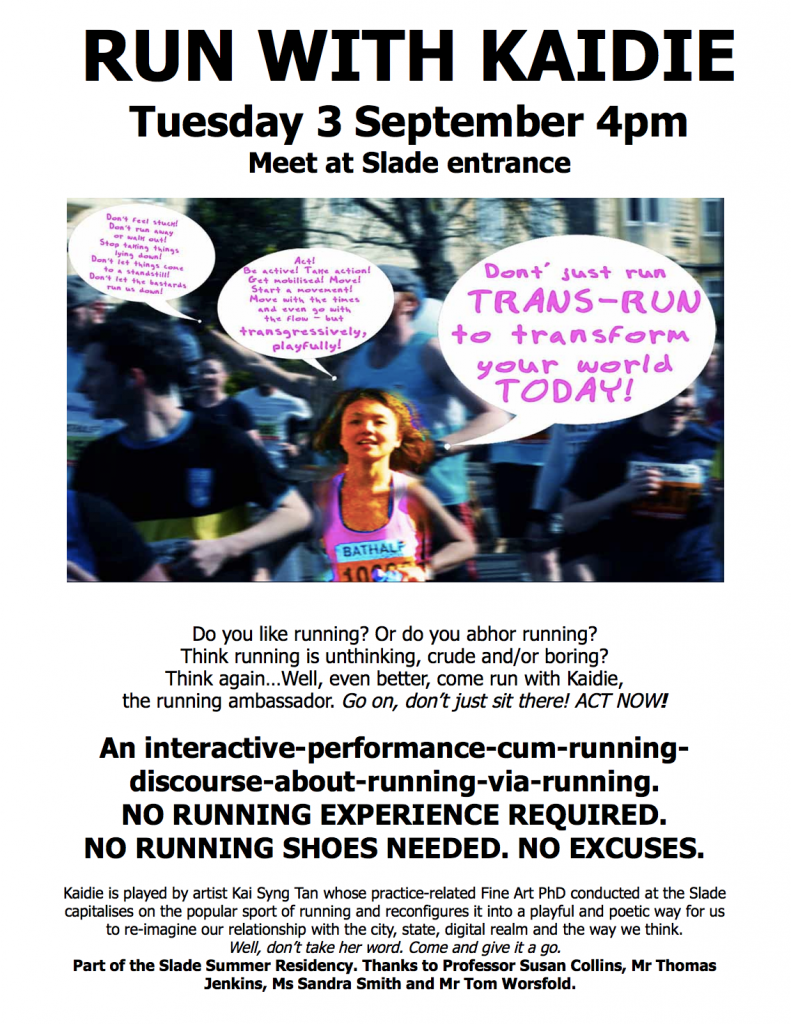

Above: An example of a Running-Game as run during Kai’s 2012 Slade Summer Residency, as ‘Kaidie’ from her Kaidie’s 1000-Day Trans-Run 12.12.2009 – 09.09.2012. Below: Poster for the game.